Meet the Bluebirds and Redbirds, the most iconic cars in the Museum’s IRT fleet!

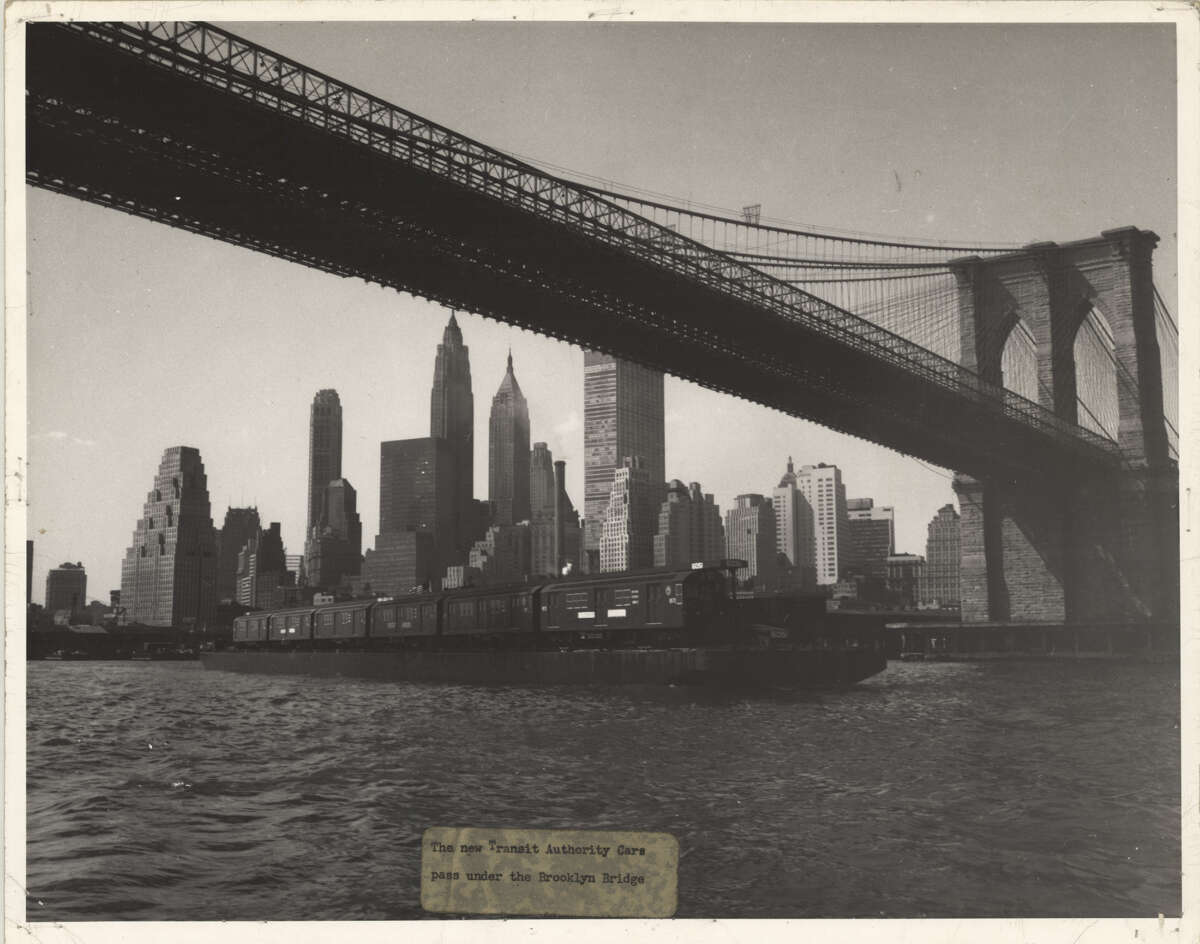

R-29 cars on the East River, 1962

New York Transit Museum Collection XX.2014.38.48

The arrival of the R-29s was cause for celebration: these cars were intended to phase out IRT cars that had been in service for 50 years. The new fleet was greeted with an aquatic parade of fireboats and police escorts.

In 1959 the first R-26 arrived in New York City. Built by American Car and Foundry, the R-26 was the first subway car to have fiberglass seats (in a salmon pink shade) and the first to not have operating cabs at both ends of the individual cars. They arrived wearing a dark olive green paint, also known as a “livery” but it was the color they’d be repainted in the mid-1980s that made them famous.

The R-26 was the first of nine types of similar-looking subway cars that would become synonymous with New York City, and as iconic as the subway token. These cars, delivered between 1959 and 1964, collectively came to be known as “Redbirds” — because of the color they were painted from 1984 until retirement in 2003. Any subway ride taken between 1959 and 2003 more than likely involved a Redbird, since nearly 2,000 of them ran on every numbered line and several lettered lines.

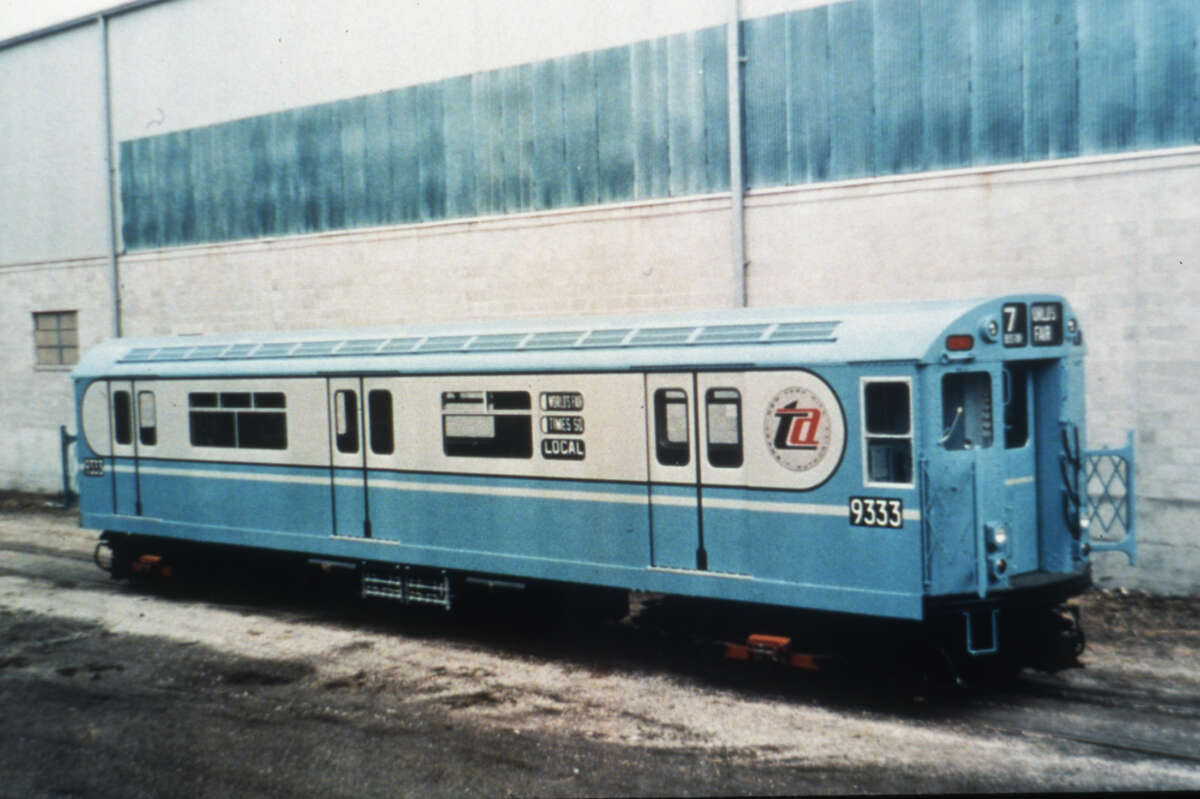

R-26 cars in a yard, c. 1960s

New York Transit Museum

Vincent Lee Collection

2005.61.55

The R-26 was the first of the cars with similar body designs that became the Redbirds. They were the lightest cars ever manufactured by American Car and Foundry, and had molded fiberglass seats, which became the standard on New York subway cars.

Boxy and industrial-looking, the cars that ultimately became Redbirds arrived at a time of great change — for better and worse — in New York City. The Redbird fleet left an indelible mark on public perception of the city and its transit system, and simultaneously captured the imaginations of millions. They still evoke fond memories to this day, especially as part of the Transit Museum’s fleet of vintage subway cars.

Which car types became Redbirds?

The “R” in car numbers such as R-33 means “rolling stock”, a rail industry term that refers to any vehicle that moves on a railway. The nine car types that became known as Redbirds were:

- R-26

- R-27

- R-28

- R-29 / R-99 (their number after being overhauled)

- R-30

- R-33 or R-33ML (ML for “Main Line”)

- R-33S

- R-36 or R-36WF (WF for “World’s Fair”)

Why did the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA) buy the Redbirds?

The Redbird story begins in 1958. The subway system was already more than 50 years old, and some subway cars had been in service since the early 1900s. The NYCTA set out to replace its oldest cars in phases, resulting in the largest fleet replacement undertaken to that point. At this time, the NYCTA fleet of passenger cars numbered 4,447, and 1,537 of those were over 35 years old — and some were over 50 — more than 34 percent of the fleet!

In 1958, after a design process intended to standardize car appearance across the former BMT, IND, and IRT services, 110 R-26 and 100 R-28 cars were ordered to replace the dated rolling stock of the IRT. A year later, in 1959, 230 R-27 and 320 R-30 cars were ordered for the BMT and IND services.

Some new subway cars had been filtered into service throughout the early 1950s, but platform extensions and expanded capacity of subway lines precluded retiring some of the oldest cars.

What colors were the cars painted before they became Redbirds?

The most famous livery the cars wore before they became Redbirds was the “Bluebird” paint scheme the R-33S and R-36WF sported when they first rolled into the system in late 1963. There were 430 of them, and World’s Fair visitors were instructed to “Follow the blue arrow” to the Queens fairgrounds.

R-33WF, c. 1970s

New York Transit Museum Collection

Intended to run only on the IRT Flushing Line (today’s 7 train), R-33WF cars were originally painted turquoise blue and white when delivered in 1963. Their cheerful hue was intended to encourage people to visit the World’s Fair in Flushing, Queens, and earned them the nickname “Bluebirds.” These cars remained blue until the mid-1970s. Car 9306 on the Museum platform is preserved in its 1970s state. The introduction of the distinctive World’s Fair blue livery wasn’t the first time a subway car was called a “Bluebird”. There was an experimental car that the BMT used in the subway from 1939 to 1955 that had the nickname first.

1970s: A rolling stock rainbow

R-29, c. 1970s

New York Transit Museum Collection

R-29 cars went into service painted the bright “Tartar Red” color. Tartar Red was one of several colors worn by the fleet that would become the Redbirds.

R-28 in Platinum Mist livery, c. 1970s

New York Transit Museum

NYCTA Photographic Unit Collection

When the MTA was formed in 1968, an initiative was taken to unify the colors and branding on all its vehicles. Since the agency’s corporate colors were silver-grey and blue, the “Platinum Mist” paint scheme was a natural choice. By 1971, nearly 1000 subway cars were painted this way.

R-36WF in Snow White livery, 1982

New York Transit Museum Collection

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, graffiti inside and outside of train cars had reached critical mass. Different deterrents were tried, including choosing new paint colors for the fleet. In what seemed a counterintuitive strategy, white was one of the colors tested.

At a cost of $2,200 per car, the white paint was formulated with a polyurethane compound resistant to markers and spray paint, as well as to shed markings easily when washed in the maintenance yards. Meant to shame graffiti writers from defacing cars that appeared clean, the trains were jokingly referred to as “The Great White Fleet.”

R-33s in “Green Hornet” livery, 1987

Photo by William R. Mangahas

Courtesy of Newkirk Images

The New York subway was no stranger to green cars; when the Independent Subway (IND) opened in 1932 all the rolling stock was painted a color similar to military vehicles of the time. This color, officially called Kale Green, was tested by the Transit Authority on 12 R-33 cars on IRT (numbered) lines.

The Train of Many Colors, 2018

Photograph by Ronald Yee

The Train of Many Colors (also referred to as TOMC) is a favorite Museum nostalgia train, and contains some of the car types that ultimately became Redbirds. The name comes from the fact that the cars are painted in schemes spanning more than 40 years of service, including Tartar Red and World’s Fair blue, mimicking some actual train consists from the late 1970s and early 1980s.

What happened to the cars in the 1980s?

In the 1980s, efforts were undertaken to change the public’s perception of the subway — and by extension, of New York City itself, turning a symbol of decline into a symbol of hope. A 1980 internal MTA report estimated that it would cost upwards of $2.5 million to remove graffiti from subways, buses, and station structures. Addressing other types of vandalism, such as broken windows, would cost another $3.5 million. Keeping subway cars in working order was also getting more expensive, due to skyrocketing material costs and less than optimal supply chains.

Car cleaning, 1973

New York Transit Museum Collection

In 1972, it cost the Transit Authority about $500,000 a year to remove graffiti from subway cars. By 1980, the cost of removing graffiti had risen to an estimated $6 million annually. Despite this, it took several years before the City and the Transit Authority were able to dedicate resources and manpower to curb the rise of graffiti on trains.

Richard Ravitch (1933 – 2023) was appointed Chairman of the MTA in 1979 and remained in that position until 1983. During his tenure, he used his financial savvy to secure the funding needed to get the system back on track. He was instrumental in the passage of the 1981 Transportation System Assistance and Financing Act, which allowed the MTA to issue bonds for major infrastructure projects.

In September of 1982, Ravitch unveiled the first five-year Capital Plan — a plan to reinvest money in the transit system that continues to this day. Along with purchases of new buses and subway cars, the Capital Plan also included funding for initiatives like the Clean Car Campaign and the General Overhaul Program (GOH).

R-33s before and after overhaul, 1988

New York Transit Museum

NYCTA Photographic Unit Collection

The General Overhaul Program (GOH), which operated from 1986 to 1991, rebuilt 1,566 subway cars from the R-26 through R-36 types at an average cost of about $272,000 per car — a significant savings relative to the cost of replacement.

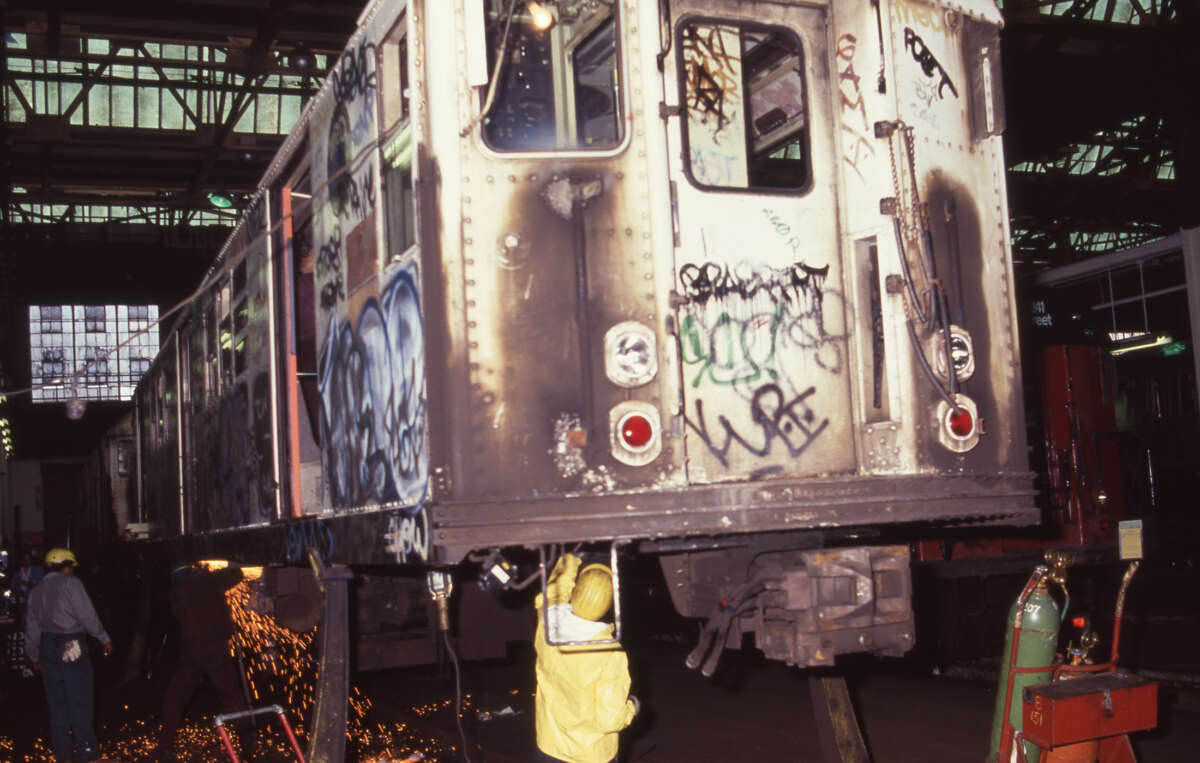

R-33 getting overhauled at 207th Street, 1988

New York Transit Museum

NYCTA Photographic Unit Collection

The 207th Street Maintenance Shop worked hard to compete with private companies who were also part of the GOH program, and in the process, streamlined the way in which subway cars are maintained. Those improved procedures are still in use today.

Although it could take over 3,000 hours to overhaul a car, once complete the cars were able to travel more miles between servicing than ever before. This allowed older cars to remain in service as ridership grew.

Redbirds at the E. 180th Street yard, c. 1980s

New York Transit Museum

NYCTA Photographic Unit Collection

Photograph by Felix Candelaria

Fox Red, also known as Tuscan Red, was the winner of the paint color experiments of the early 1980s and was the last step in the overhaul process. A traditional railroad color because it hides stains due to metal dust, it was colloquially known as “Gunn Red,” after David Gunn, who served as President of the New York City Transit Authority from 1984 to 1989. This is what gave the Redbirds their name and was the last fully painted exterior in New York Subway history. Pictured are R-26, R-28, and R-29 cars in storage at 180th Street, after the Redbird livery was applied. Painting similar-bodied cars one color made the fleet look clean and modern.

Last Redbird run, November 3, 2003

Photograph by Ralph Curcio

New York Transit Museum

Ralph Curcio Slide Collection

Gift of Daniel G. McFadden

2016.12.1.31.2

The last run of the Redbirds, on the IRT Flushing Line (7 train), was a bittersweet celebration. Hundreds of people rode the last 11-car train from Grand Central to Flushing Meadows-Corona Park.

How does the NYTM preserve these trains?

Like people, each train car is different, even if they are the same car type. A team of NYTM volunteers works closely with Car Equipment and other NYCTA departments to prepare our fleet for Nostalgia Rides and other events. Each car that is in service at one of these events has undergone the same safety testing as any other subway car in revenue service.

One of the most fun parts of the restoration work with the NYTM vintage fleet is choosing the livery the car will wear. In the case of the Redbirds, Bluebirds, and other cars that might appear on the Train of Many Colors, there are many colors to choose from; the history spans almost 50 years in which these cars were in service. The Museum and the restoration team discuss what cars will be restored to which era — some are restored to a specific year, and others to a specific decade. Research is done in the Museum’s archive to find the names of the manufacturers and paint colors from the 1950s and ‘60s to help match what the cars looked like when they were new. Photographs are consulted, and small samples are taken from the existing cars to help as well.