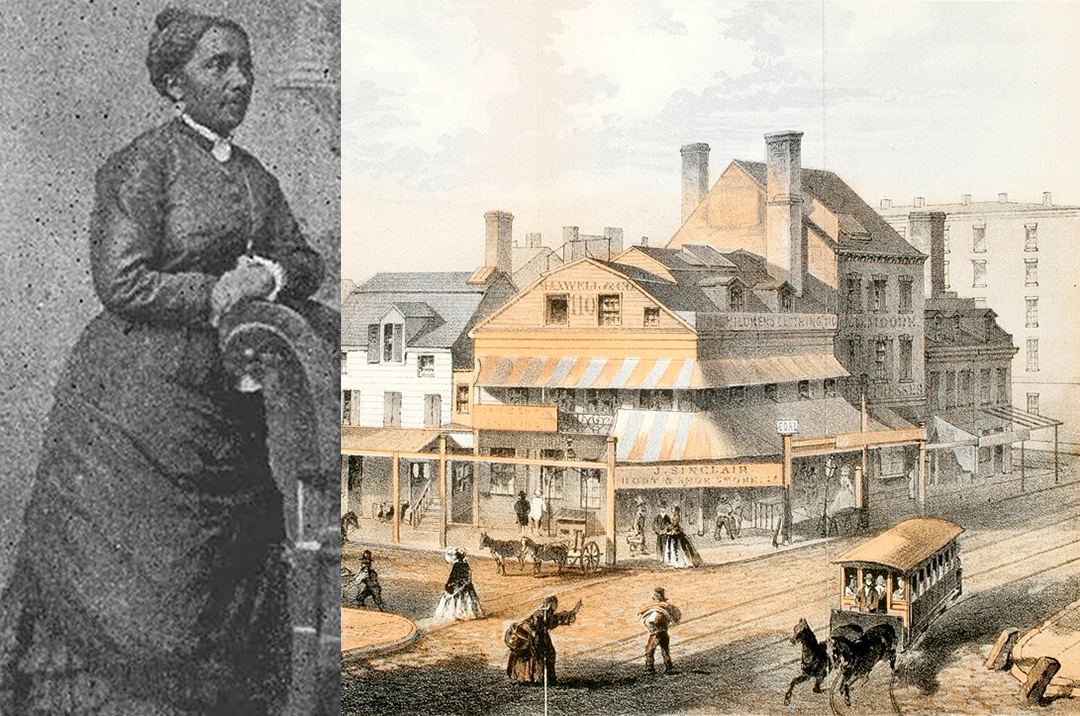

100 years before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat, a 24-year-old Black New Yorker stood her ground on a streetcar.

With courage and perseverance, she won the first recorded legal victory for equal rights on public transportation.

HER NAME WAS ELIZABETH JENNINGS GRAHAM. DO YOU KNOW HER STORY?

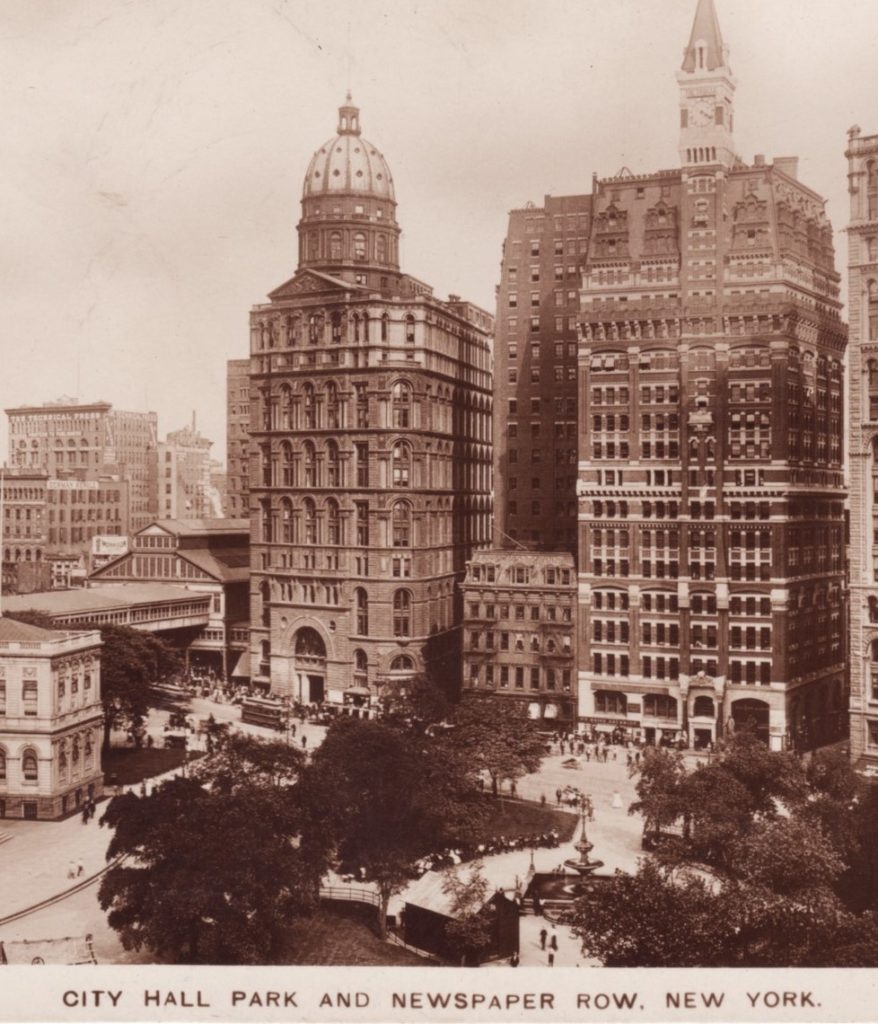

On a hot Sunday morning in July 1854, Elizabeth Jennings, a 24-year-old Black schoolteacher on her way to church, boarded a Third Avenue Railroad Company horsecar at Pearl and Chatham Streets in lower Manhattan. Soon after boarding, Jennings was ordered to get off the horsecar and told to wait for a car that served African American passengers.

At the time, all public transportation in New York City was privately owned. Some omnibuses and horsecars displayed signs announcing “Colored Persons Allowed,” but these segregated vehicles were few and far between. New York City’s Black residents were expected to walk; public transportation was rarely available.

Jennings ignored the conductor’s orders and resisted his attempts to remove her physically. Finally, with the aid of a policeman, he succeeded in forcing her off.

“The conductor undertook to get her off, first alleging the car was full, when that was shown to be false. He pretended the other passengers were displeased at her presence. But [when] she insisted on her rights, he took hold of her by force to expel her. She resisted. The conductor got her down on the platform, jammed her bonnet, soiled her dress and injured her person. Quite a crowd gathered. But she effectually resisted. Finally, after the car had gone on further, with the aid of a policeman they succeeded in removing her.”

— New York Tribune, February 1855

The Black community was enraged, and the day after the incident they held a rally at Jennings’ church. Just as Rosa Parks would a century later, Jennings took her case to court. She sued the driver, the conductor, and the Third Avenue Railway.

Remarkably, Jennings was represented by a 24-year-old lawyer, Chester A. Arthur. Then just a junior partner at Culver, Parker, and Arthur, he later became the 21st President of the United States.

In 1855 Judge Rockwell of the Brooklyn Circuit Court ruled: “Colored persons if sober, well behaved and free from disease, had the same rights as others and could neither be excluded by the rules of the company, nor by force or violence.” Jennings won her suit and was awarded damages.

Elizabeth Jennings Graham “deserves a place of honor in the history of civil rights in New York.”

— John H. Hewitt

Jennings’s victory served as a powerful catalyst in the fight for equality on New York’s public transit vehicles, but it didn’t end segregation once and for all. It would take nearly twenty years before all New York City streetcars were desegregated.

Within a month of Jennings’s victory, a Black man named Peter Porter was refused a ride on an Eighth Avenue Railroad Company car along with his wife and four other women. He sued, too, but settled out of court, and the company agreed to let black people ride in the same cars as whites.

In 1873, the New York State legislature passed the Civil Rights Act, which explicitly outlawed discrimination on public transportation in the city. Thus, more than thirty years before the New York City subway opened, all transit lines in New York City were integrated by law.

Images courtesy of the Kansas State Historical Society and the New York Transit Museum