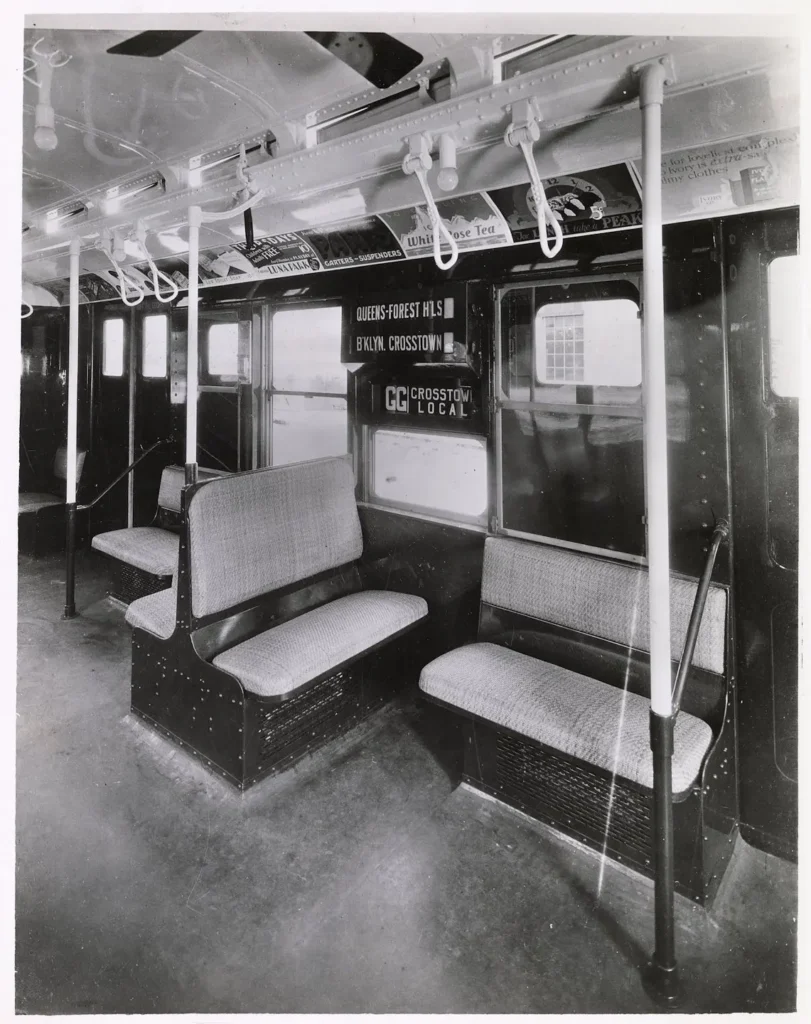

The cars entered service between 1931 and 1940 and remained on the rails until they were replaced between 1968 and 1977. The last of this broad grouping of cars were removed from passenger service in 1977.

Pictured here, the R1 cars first entered the New York City subway system via Bush Terminal in Brooklyn.

R1 cars being unloaded at Bush Terminal, c. 1931

Lonto / Watson Collection

New York Transit Museum